Hello Everyone,

Welcome to my final reflection as I look back at my learning journey over the past three months!

Context

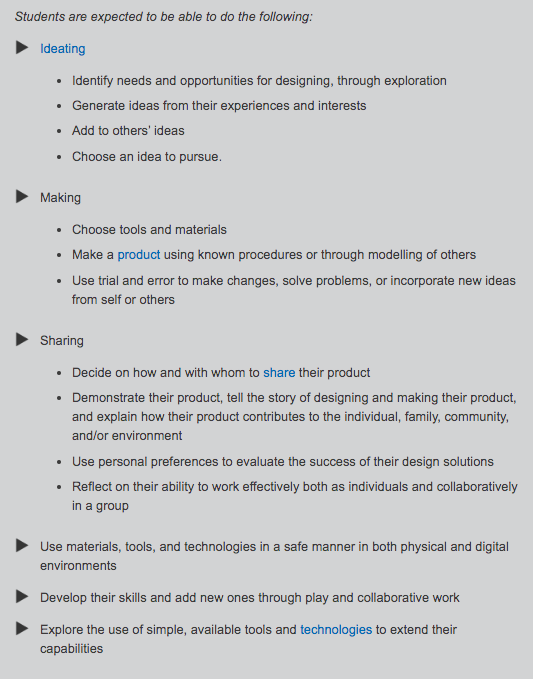

I am fortunate to teach Kindergarten at an International Baccalaureate World School in North Vancouver. The IB mission very much aligns with the Redesigned BC Curriculum in its open-ended, inquiry-based nature. This mandated curriculum for students from K-12 includes a subject called Applied Design, Skills, and Technology (ADST). For Kindergarten, the expected learning outcomes are as follows:

(Source: https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/curriculum/adst/k)

Additionally, the government of BC also offers a Digital Literacy Framework (PDF) which outlines six characteristics based on the National Educations Technology Standards for Students (NETS•S) standards. These characteristics encompass the skills considered necessary to be successful learners in the 21st century. To further elaborate on these characteristics, The National Council of Teachers of English (NTCE) has created a set of of 21st century literacies. The NTCE (2013) posits that literate 21st century global citizens are required to:

- Develop proficiency and fluency with the tools of technology

- Build intentional cross-cultural connections and relationships with others so to pose and solve problems collaboratively and strengthen independent thought;

- Design and share information for global communities to meet a variety of purposes;

- Manage, analyze, and synthesize multiple streams of simultaneous information;

- Create, critique, analyze, and evaluate multimedia texts;

- Attend to the ethical responsibilities required by these complex environments.

With these technological competencies in mind, my inquiry process was far from linear as I initially struggled with narrowing my focus. At first, I was interested in the home-school connection because I was struggling to find an effective way to communicate with my Kindergarten families. This challenge lead me to consider:

- Does technology help to bridge the gap between home and school or does it widen it?

Once I began my first IB unit of inquiry with my Kindergarten students I considered:

- How can technology serve as a tool for authentic knowledge construction in the early years?

- How can technology support inquiry-based learning within an early years context?

It wasn’t until I read Alison Galloway’s MEd project about a Reggio Emilia inspired makerspace that I was inspired to look into the following inquiry:

- Does technology support or disrupt the Reggio Emilia philosophy?

It took me several weeks of reading and conversations with my learning pod and the network of teachers in my school district to realize that my inquiry had actually developed into how to authentically and effectively integrate technology in an early years learning environment while honouring the Reggio Emilia philosophy.

I am passionate about the Reggio Emilia philosophy and consider it to be the leading force behind my pedagogical practices. The Reggio Emilia philosophy emphasizes the environment as the third teacher, the image of the child, documentation, and community connections. Therefore, my inquiry topic arose out of a sense of discomfort when envisioning the warm, inviting environment, natural materials and childcentered approach of the Reggio Emilia philosophy in comparison to a cold, sterile room filled with rows of isolated computers. However, as I delved into the research and connected with others, it became glaringly evident that technology plays a large role in a 21st century Reggio Emilia inspired early learning environment. It was time to face my misconceptions.

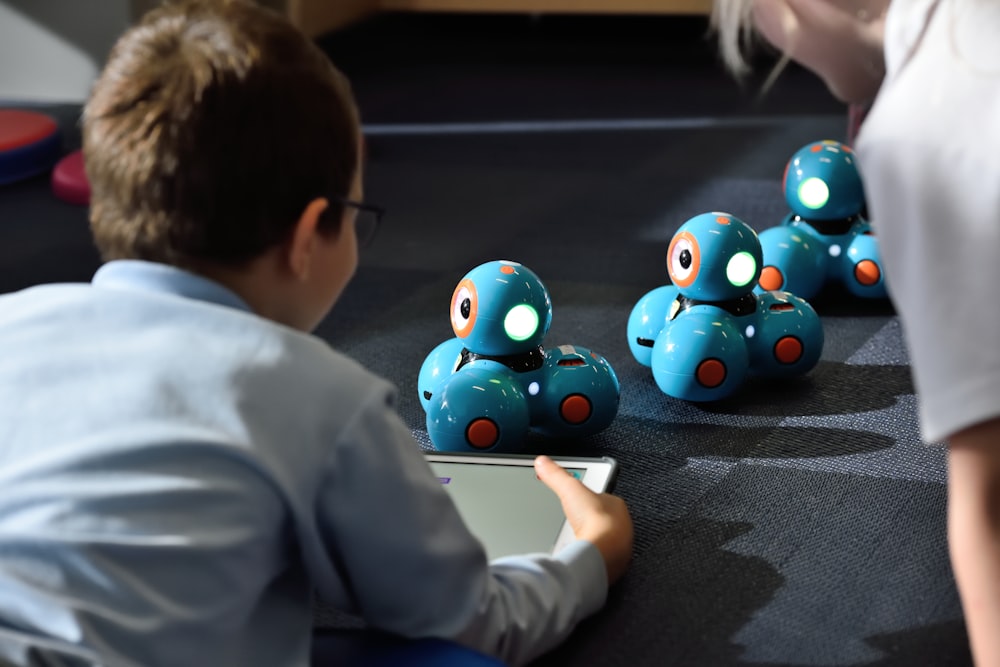

The Environment as the Third Teacher

Take one step into our classroom and it is evident that the learning environment reflects the Reggio Emilia philosophy. Our room includes soft, home-like furnishings, dim lighting, natural materials, loose parts, and the children as well as their families are honoured throughout. The environment acts as a third teacher, offering students opportunities to learn and play together while exploring their surroundings. Through my inquiry I learned about Makerspaces and how they can create an environment in which everyday materials as well as digital materials are offered as provocations for students. By meeting with Alison Galloway, reading her MEd project, and visiting her website, it became evident that Makerspaces and the Reggio Emilia philosophy reflect one another. Following the makerspace movement Bers, Strawhacker & Vizner (2018) suggest that providing children a mixture of digital and non-digital tools such as robotic kits, circuitry materials, vinyl cutters, powered hand tools, robotics kits, cardboard, clay, scissors, tape, and metal brads may be a good first step to technology in a Reggio Emilia inspired early learning environment.

The Image of the Child

My students are trusted and valued as competent, capable navigators of their own learning. They have full access to their environment. It is common to see a child standing on a chair to help themselves to something up in the cupboard or getting up on the windowsill to use the natural light for their drawing. Yes, safety is prioritized in the classroom but so is student agency. For instance, some of my students found a picnic basket yesterday which contained real plates, utensils, and cups. Immediately the boys wanted to use their new-found tools in our home-centre. Instead of shutting down this potentially risky play, I brought over an appleand demonstrated the appropriate way to cut using the found tools. The boys took turns cutting the apple and enjoying, quite literally, the fruits of their labour.

As demonstrated, curriculum is emergent as children explore their surroundings. Through my research I was introduced an article by Hong and Trepanier-Street (2004) which discussed KidPix and Kidspiration–digital platforms for children to express their ideas. These platforms reaffirm the image of child as competent and capable by offering them the tools to demonstrate their thinking more complexly and accurately than if they were to use conventional tools.

Documentation

Documentation occurs multiple times a day in our classroom. I frequently hear, “Ms. Pulice, take a picture!” Pictures, videos, and voice recordings enable us to capture moments and creations that would otherwise disappear after clean up. The students advocate for the documentation of their work and will often ask for it to be shared with their families. They take pride in their work and feel a sense of gratification knowing that their families will see what they have accomplished at school. This ongoing documentation allows us to look back, reflect, and revise our learning. The students have the opportunity to build off of their prior work and knowledge while I have the opportunity to revisit lessons and extend students’ thinking. My learning pod, Emily and Trisha, shared with me their successes with the Seesaw and Freshgrade apps for documenting students’ work. They both work with older primary students (Grades 1-2) so they also find that students have agency when documenting their own learning. In the Kindergarten context, students can still have a voice in what is being documented even if they are not the ones directly accessing the app. Rinaldi (2006) found that documentation also motivates students because they feel that their work is being valued. Through the Kindergarten teachers network in my school district I was introduced to the HP Instant Ink program for teachers. The program provides teachers with the tools to honour their students’ work by offering affordable coloured printing options.

Community Building

Students work together and learn from each other while also sharing with their families, the community at our school and in the district. I see children helping each other through their inquiries and sharing their knowledge through play. Families in the digital age are connected to their children’s learning through online platforms. My learning pod shared FreshSchools with me which is a platform which enables families to access all school information in one easy place. Through my school, I have been introduced to Managebac which is a platform specifically for IB schools which also enables students and teachers to document and share learning online. Lim and Cho (2019) found that mobile documentation is an effective way to connect with 21st century families and have them more present in their children’s educational journeys. Not only can online platforms support family engagement, they can also be used to reach the greater community and invite knowledge sharing from around the world. These connections can build rich sites of knowledge construction for young learners.

Enduring Understandings

The open-ended, inquiry process has been uncomfortable and yet has offered many opportunities for failure as well as growth. Through my own inquiry trials and tribulations I have realized how challenging open-ended learning must be for my young students. However, I have also seen the great value in sitting in the discomfort. I came to many roadblocks throughout my inquiry including a lack of research on my topic as well as reframing my thinking about the Reggio Emilia philosophy which I originally thought I was very knowledgable about. There was a large component that I was missing in my practice and this inquiry has lead me to the realization that technology is not separate from the Reggio Emilia philosophy and is instead imbedded within in it as a 21st century literacy. Moving forward I intend to weave the following enduring understandings from my inquiry into my practice:

- Technology should be readily available for children, coinciding with the loose parts and natural materials in the learning environment.

- Children should have the opportunity to be creators, not just consumers of technology.

- Technology should be used as a tool to build community through documentation and sharing.

- Technology should support multimodality and be considered as one of children’s “one hundred languages.”

- As per the SAMR Model, technology should be used primarily for the modification or redefinition of a task as opposed to simple substitution or augmentation.

Thank you for following my inquiry journey. I look forward to using this platform to document my learning as I refine my search for my final MEd project.

Take care,

Miss P.💕

References

BC Ministry of Education. (n.d.). BC’s New Curriculum. Retrieved from, https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/curriculum/social-studies/2

BC Ministry of Education. (2016). Digital Literacy Framework. Retrieved from http://www.bced.gov.bc.ca/dist_learning/dig_lit_standards.htm

Bers, M., Strawhacker, A., & Vizner, M. (2018). The design of early childhood makerspaces to support positive technological development two case studies. Library Hi Tech, 36(1), 75-96. doi:10.1108/LHT-06-2017-0112

Galloway, A. (2015). Bringing a reggio emilia inspired approach into higher grades to 21st century learning skills and the maker movement (Unpublished master’s project). University of Victoria, Victoria, BC

Hong, S. B., & Trepanier-Street, M. (2004). Technology: A tool for knowledge construction in a reggio emilia inspired teacher education program. Early Childhood Education Journal, 32(2), 87-94. doi:10.1007/s10643-004-7971-z

Lim, S., & Cho, M. (2019). Parents’ use of mobile documentation in a reggio emilia-inspired school. Early Childhood Education Journal, 47(4), 367-379. doi:10.1007/s10643-019-00945-5

NTCE. (2013). The NCTE Definition of 21st Century Literacies. Retrieved from http://www2.ncte.org/statement/21stcentdefinition/

Rinaldi, C. (2006). In dialogue with Reggio Emilia: Listening, researching and learning. New York: Routledge

I very much strive to align my teaching practices with the Reggio Emilia philosophy and I believe this is evident in the ways in which the learning environment has been set up. I always associate the Reggio Emilia philosophy with loose parts and natural materials so I was surprised to come across the work of Galloway (2015), which examined the Reggio Emilia approach in relation to technology and the Maker Movement. As indicated by Galloway (2015) both approaches fit very nicely with the

I very much strive to align my teaching practices with the Reggio Emilia philosophy and I believe this is evident in the ways in which the learning environment has been set up. I always associate the Reggio Emilia philosophy with loose parts and natural materials so I was surprised to come across the work of Galloway (2015), which examined the Reggio Emilia approach in relation to technology and the Maker Movement. As indicated by Galloway (2015) both approaches fit very nicely with the  most prominent ways in which technology was present in both the Reggio Emilia approach and the Maker Movement was through documentation. Both approaches offer great emphasis on making thinking and learning visible. In Kindergarten, learning typically emerges through play which provides a challenge to teachers who are looking for evidence of learning for assessment and reporting. Ideally, I would want regular access to a class set of iPads which my students could use to take pictures, videos, and/or voice recordings of their work to document their own learning. A few years ago in

most prominent ways in which technology was present in both the Reggio Emilia approach and the Maker Movement was through documentation. Both approaches offer great emphasis on making thinking and learning visible. In Kindergarten, learning typically emerges through play which provides a challenge to teachers who are looking for evidence of learning for assessment and reporting. Ideally, I would want regular access to a class set of iPads which my students could use to take pictures, videos, and/or voice recordings of their work to document their own learning. A few years ago in

This year, my options for home-school communication have changed due to my relocation to a new school community. To maintain a sense of order and consistency for families I adopted the communication tool of my Kindergarten colleagues. Kindergarten students do not typically own a planner due to their limited writing abilities so instead the kindergarten teachers at my school use what they call a “back and forth folder.” The folder contains important information regarding the IB PYP and the Zones of Regulation as well as a communication page for families and the classroom teacher to write notes to each other. The front pocket is for documents, artwork, notices, etc. that are meant to be “left” at home and the back pocket is meant for those items that are meant to come “right” back to school. The kindergarten teachers also have blogs which provide information about the current IB Unit of Inquiry and scheduling for sharing. I tried these options for a few weeks but quickly realized that they weren’t true to my preferred methods of communication. I very much believe that communication is a two-way street and that there should always be an opportunity for the receiver of a message to respond. With this belief in mind, I created a

This year, my options for home-school communication have changed due to my relocation to a new school community. To maintain a sense of order and consistency for families I adopted the communication tool of my Kindergarten colleagues. Kindergarten students do not typically own a planner due to their limited writing abilities so instead the kindergarten teachers at my school use what they call a “back and forth folder.” The folder contains important information regarding the IB PYP and the Zones of Regulation as well as a communication page for families and the classroom teacher to write notes to each other. The front pocket is for documents, artwork, notices, etc. that are meant to be “left” at home and the back pocket is meant for those items that are meant to come “right” back to school. The kindergarten teachers also have blogs which provide information about the current IB Unit of Inquiry and scheduling for sharing. I tried these options for a few weeks but quickly realized that they weren’t true to my preferred methods of communication. I very much believe that communication is a two-way street and that there should always be an opportunity for the receiver of a message to respond. With this belief in mind, I created a